So, Novo Nordisk just dropped $5.2 billion on a company called Akero Therapeutics. The stock market cheered (prompting headlines like Why Akero Therapeutics Stock Trounced the Market on Thursday), Akero shareholders are popping champagne, and the press releases are overflowing with enough corporate self-congratulation to make you gag.

And I’m just sitting here thinking: are we really supposed to be impressed by this?

This isn’t some bold, visionary leap into the unknown. This is the most predictable, paint-by-numbers acquisition I’ve seen all year. Novo Nordisk, the company that basically owns the obesity market with Wegovy, is sitting on a mountain of cash so high it’s probably visible from space. What do you do with all that money? You buy the next logical thing. It's like a video game player who just beat the final boss and is now methodically running around the map collecting all the remaining power-ups. MASH—this nasty obesity-linked liver disease—is the next big side quest, and Akero just happened to be holding the treasure map.

This is a bad move. No, 'bad' doesn't cover it—this is just… inevitable. It’s the corporate equivalent of gravity. A small, innovative company gets a promising drug, a giant with a fat wallet swoops in, and the story ends. The whole thing feels less like a breakthrough and more like a spreadsheet calculation finally hitting its target number.

You have to hand it to their communications department. The quotes are masterpieces of saying absolutely nothing. Novo’s CEO, Mike Doustdar, says this deal "embodies Novo Nordisk’s relentless ambition to move faster, go further." Let me translate that for you: "Our patent on semaglutide won't last forever, and we need to buy our next revenue stream before Wall Street notices."

Then you get the chief scientific officer, Martin Lange, talking about how Akero's drug, efruxifermin, "complements Novo Nordisk's leading portfolio." Complements? Give me a break. It doesn't complement it; it completes it. They're not building a well-rounded meal; they're building a monopoly on the entire metabolic disease food chain, a goal made clear in their own announcement: Novo Nordisk to acquire Akero Therapeutics and its promising phase 3 FGF21 analogue to expand MASH portfolio. First, they sell you the drug that helps you lose weight. Then, they sell you the drug that fixes the liver your obesity destroyed. What's next, a Novo-branded line of low-calorie snacks?

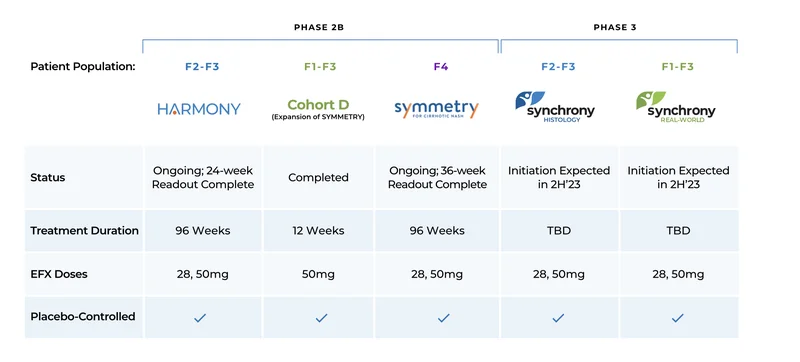

They keep throwing around phrases like "best-in-class" and "first-in-class." And look, the Phase 2 data for this EFX drug does look good, especially for patients with the worst stage of liver scarring. It's the only drug to show it can actually reverse that kind of damage. But what happens to that innovative spark once it's swallowed by a corporate behemoth with 78,000 employees? Does the scrappy Akero team get to keep running things, or are they now just another department reporting to a committee that reports to a subcommittee?

And that CVR—the extra $6 per share shareholders get if the drug gets FDA approval by 2031. Don't let them fool you into thinking that's some generous bonus. That’s just Novo Nordisk hedging its bets. It's a clever way to cap their upfront risk and make Akero’s investors share in the potential failure. If the drug works, they pay a little more. If it flops in Phase 3, they just saved themselves half a billion dollars. It's a win-win for them, and we're supposed to applaud their financial acumen. Offcourse we are.

Honestly, the part that gets me is the sheer lack of imagination. Big Pharma's R&D model isn't about discovery anymore; it's about acquisition. Why spend a decade and billions of your own dollars trying to invent something new when you can just let a hundred small biotechs do the risky work, then swoop in and buy the one that gets lucky? It's a more efficient use of capital, I guess, but it feels so soulless. It turns the life-and-death struggle of medical research into just another M&A transaction.

We're told this is about tackling "one of the fastest-growing metabolic diseases of our time." And maybe, on some level, it is. But it's also about ensuring that when the treatment for that disease finally arrives, the logo on the box is the same one that's been on all the other boxes. It's about market consolidation, plain and simple.

So what are we, the public, left with? The promise of a new drug, which is great. But it'll come at a price set by a near-monopoly, developed by a team that's been absorbed into a corporate structure, and marketed as another victory for a giant that's simply too big to fail. This isn't a story of innovation. It's a story of consolidation. And it's a story we've seen a thousand times before.