Here is the feature article written in the persona of Julian Vance.

*

There’s a category of market analysis that always gets clicks: the "dirt cheap" stock pitch. The premise is seductive. It suggests the market, in its infinite wisdom, has somehow overlooked a gem—a solid, cash-gushing business trading for a pittance. Recently, Verizon Communications and Carnival Corp have been cast in this role, presented as 2 Dirt Cheap Stocks to Buy With $300 Right Now.

The argument hinges on simple, forward-looking valuation metrics. Verizon, the telecom behemoth, trades at a mere eight times forward earnings. Carnival, the cruise line titan, is priced at just 12 times next year’s projected profits. On the surface, these numbers scream "undervalued."

But my work has taught me that a low price-to-earnings multiple is often just that: a low price. It isn't inherently a signal of a bargain; more frequently, it's a quiet admission of risk. The market isn't stupid. It's a collective pricing mechanism that, while not always perfect, rarely gives away quality for free. The real question isn't whether these stocks are cheap, but why they are cheap. And the data suggests the reasons are far from trivial.

Let’s start with Verizon. The bull case is straightforward and has been for years. The company is a utility-like "money machine," generating enormous free cash flow from its 146.1 million accounts. Its most alluring feature is a dividend yield that hovers around 7%—to be more exact, 7.1% at the time of the analysis—the highest in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. For an income-focused investor, this is a powerful magnet.

The problem is what lies just beneath that stable surface. A look at the most recent third-quarter results reveals a critical fissure in the foundation. While headlines might proclaim that Verizon Sees Broadband Gains Amid Mixed Financial Results, the company also missed on revenue. More alarmingly, its core Consumer segment reported a net loss of 7,000 wireless retail postpaid phone subscribers.

This is the part of the report that I find genuinely puzzling from a bull's perspective. A mature telecommunications carrier losing postpaid phone customers—the most lucrative and stable part of its user base—is a significant red flag. It points to competitive pressure and potential market share erosion. While the company saw strong growth in broadband net additions (306,000 in the quarter), this feels like patching a leak on a battleship with duct tape. Is the new revenue from fixed wireless access enough to offset the slow decay of the primary profit engine?

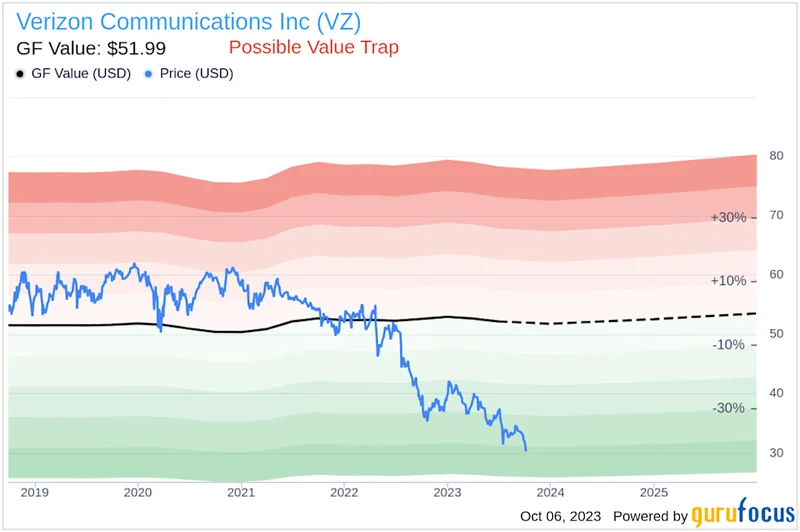

And this brings us back to the valuation. The stock trades at eight times forward earnings, but it also carries a massive debt load, so much so that its enterprise value is roughly double its market capitalization. That high dividend isn't a gift; it's a commitment that has to be serviced alongside that debt. When your core consumer business is showing signs of stagnation, how sustainable is that payout in the long term without sacrificing necessary network investment? The market is pricing in this exact risk. It sees a utility, yes, but one whose pipes are starting to show their age.

Carnival presents a different, though equally complex, picture. The company’s story is one of a dramatic post-pandemic rebound. The headline numbers are undeniably impressive: ten consecutive quarters of record revenue and a dozen straight quarters of beating analyst profit targets. With half of next year's capacity already booked, momentum appears strong.

But "record revenue" is a term that demands context. This isn't a company growing from a stable, pre-2020 baseline. This is a company that was forcibly shut down for over a year. Its recovery is like watching a sprinter finally allowed to leave the starting blocks a full minute after the race began; their initial velocity looks incredible, but it tells you very little about their sustainable long-term pace. The real test isn't just growth, but profitable growth that exceeds pre-crisis levels in a meaningful way. Are we seeing that, or are we just seeing the predictable snap-back from an artificial bottom?

The analysis celebrating Carnival as "dirt cheap" points to its net yield—an industry metric for profitability—hitting an all-time high. This is a valid and important data point. However, unlike its rival Royal Caribbean, Carnival has not resumed paying a dividend. This means the entire investment thesis rests on capital appreciation, which in turn rests on the market "re-rating" the stock to a higher multiple.

Why hasn't it? Perhaps because the market understands the cyclical nature of the travel industry and the immense capital expenditures required to maintain and expand a fleet of ships. The company is performing well now, during a period of intense "revenge travel." But what happens when that pent-up demand normalizes? Will consumer discretionary spending remain this robust if economic conditions tighten? A valuation of 12 times forward earnings for a capital-intensive, non-dividend-paying company in a notoriously cyclical industry doesn't sound "dirt cheap." It sounds, frankly, quite reasonable.

Ultimately, the narrative that Verizon and Carnival are misunderstood bargains falls apart under closer scrutiny of the operational data. These stocks aren't cheap because the market is overlooking them. They are priced precisely where they are because the market has weighed the risks.

For Verizon, the price reflects the existential threat of a stagnating core wireless business burdened by significant debt, even as its dividend remains attractive. For Carnival, the price reflects the inherent uncertainty of a post-rebound travel market and the cyclical risks that have always defined the industry.

Calling them "dirt cheap" is a compelling headline. But it’s a misnomer. These companies don’t have a clearance sticker on them; they have a price tag that accurately reflects the merchandise. And for a discerning analyst, there's a world of difference between the two.