Andrew Ross Sorkin, a man who has spent his career chronicling financial titans and their follies, is anxious. In a recent sit-down with 60 Minutes, he drew a stark parallel between our current AI-fueled market euphoria and the speculative frenzy of the late 1920s. It’s a comparison designed to grab headlines, and it works. But beneath the historical drama lies a quantitative question: is the market’s current structure a genuine technological revolution, or is it just the same old speculative leverage dressed up in a new digital narrative?

Sorkin's thesis, as he recently explained, is that AI boom propping up economy as some guardrails are coming off, journalist Andrew Ross Sorkin warns. He posits we’re in either a gold rush or a sugar rush, and the distinction is critical. A gold rush creates lasting infrastructure and wealth. A sugar rush delivers a temporary high followed by a debilitating crash. Looking at the data, the capital expenditure is undeniable. Hundreds of billions are flowing into data centers, chips, and software. This isn't imaginary.

The problem is one of correlation versus causation. Is this massive investment driving broad economic health, or is it an isolated phenomenon whose market capitalization is distorting our perception of the whole? It feels like we’ve bolted a Formula 1 engine onto the chassis of a 1995 sedan. The vehicle is moving at an astonishing speed, but the frame, the transmission, the very foundation of the "real economy," shows signs of strain. The market is up, but underlying indicators suggest softness. This is the central discrepancy that gives Sorkin’s anxiety its weight. And this is the part of the current narrative that I find genuinely puzzling: the almost willful ignorance of this disconnect. We celebrate the speed of the engine without ever checking the integrity of the chassis.

The parallels to 1929 become more acute when you examine the financial instruments involved. A century ago, the innovation was consumer credit and margin loans. As Sorkin notes, debt was once considered a moral failing. Then, General Motors and Wall Street reframed it as "access" and "democratization." It allowed people with 10% of the capital to control 100% of a stock, amplifying gains on the way up and guaranteeing total annihilation on the way down. Today, the language is identical, but the products have changed.

The modern push isn't for margin loans; it’s for access to private markets. We’re told it’s "unfair" that only the wealthy could invest in Uber or Facebook pre-IPO. Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, is now a chief evangelist for this new gospel, suggesting we open up retirement 401(k)s—the bedrock of cautious, long-term saving—to the high-risk, high-reward world of venture capital and private equity. His firm, BlackRock, stands to gain substantially from management fees on these new products (their recent Bitcoin ETF is a prime example).

Fink argues that with a long-term horizon, investors will "do fine." This is a dangerously simplistic view. Private assets are illiquid, opaque, and notoriously difficult to value. Public companies are subject to stringent SEC disclosure rules. Private companies are not. Pushing these assets into 401(k)s isn't democratizing wealth; it's democratizing risk. It's asking the least sophisticated investors to provide exit liquidity for the most sophisticated ones. What is the real incentive here? Is it to generate alpha for retail investors, or is it to create a vast, new pool of capital to absorb venture-backed companies that may not be ready for the scrutiny of public markets?

This is all happening, as Sorkin correctly points out, as the guardrails are coming off. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has been weakened. SEC rules are being loosened. The narrative of "democratization" is a powerful tool to dismantle the very protections that were put in place to prevent another 1929. We are systematically removing the brakes from the car while the AI engine pushes it faster than ever.

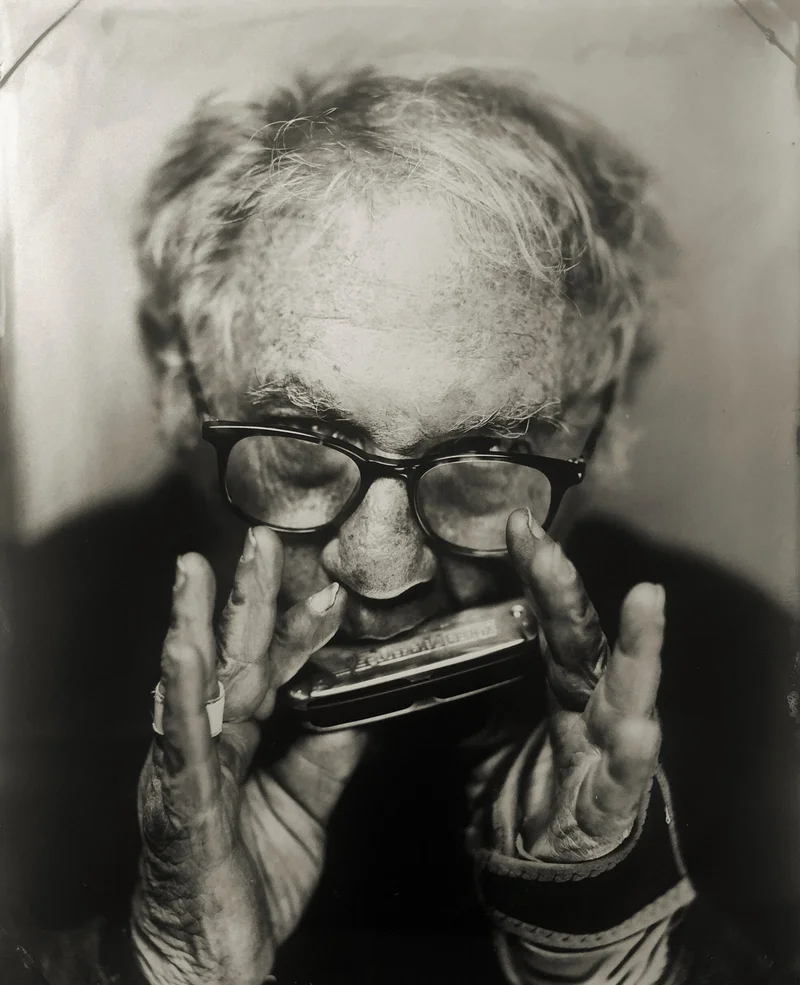

The crypto market offers a perfect microcosm of this dynamic. Fink now sees a role for crypto as an alternative to gold, a stunning reversal from his previous skepticism. Yet Sorkin’s own bizarre experience with the "Sorkin Coin" illustrates the true nature of this unregulated space. A joke on television spawned a cryptocurrency with a peak daily trading volume of around $170 million—to be more exact, it was a reported $170 million in a single day, a crucial distinction that highlights the speculative frenzy over any semblance of underlying value. It was a pump-and-dump scheme, pure and simple. Now, imagine that kind of volatility being pitched as a reasonable component of your retirement savings.

Sorkin assures us a crash will happen. He just can’t say when. That’s the oldest truth on Wall Street. The timing is always uncertain, but the cycle is not. When confidence evaporates, it happens in an instant. The anxiety he feels isn't just about history repeating itself. It’s about recognizing that while the technology and the terminology have evolved, the underlying human behaviors of greed, speculation, and the clever repackaging of risk have not changed at all.

The story being sold is one of opportunity. The quiet truth is that the financial architecture is being reconfigured to transfer risk. In 1929, the small investor was wiped out by margin calls on public stocks. In the next downturn, the damage will be done by illiquid, overvalued private assets buried deep inside retirement accounts, sold under the banner of "fairness." The system isn't broken; it's being tuned to perfection. The risk hasn't been eliminated; it's just been rerouted to a different destination—your 401(k).