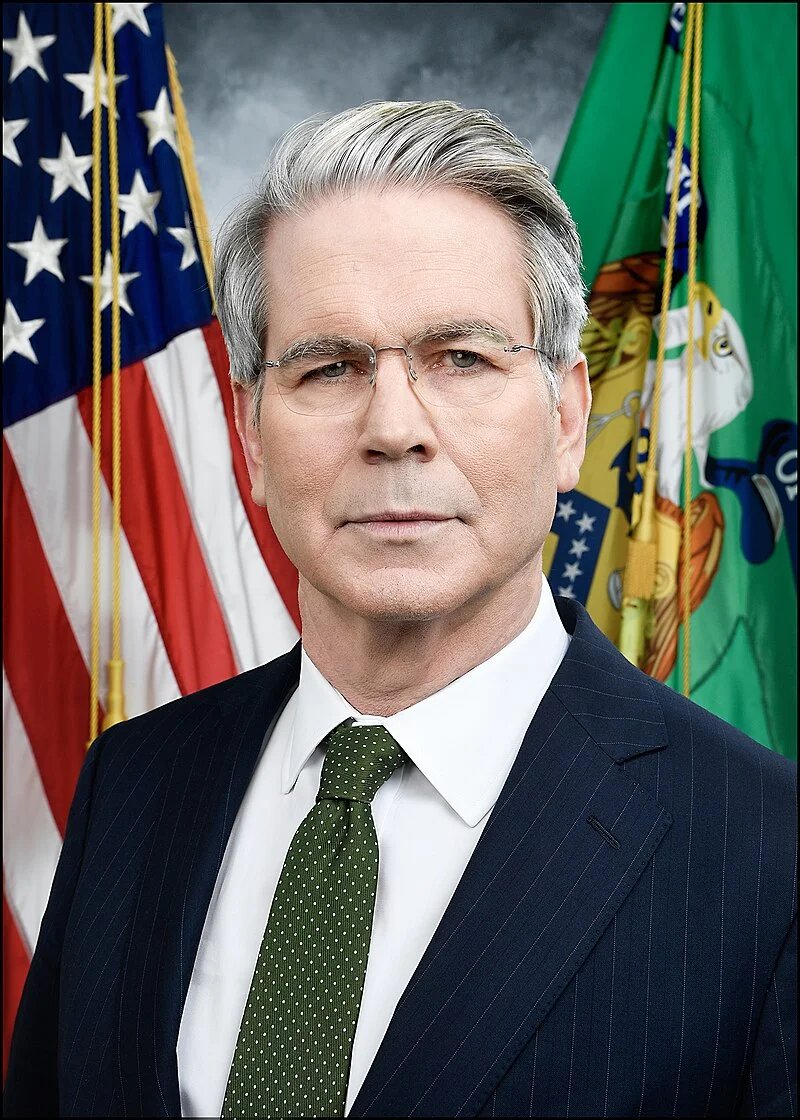

There are moments in political theater that are so perfectly dissonant, so jarringly out of tune with reality, that they demand closer analysis. One such moment arrived this week from Kuala Lumpur, where Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, a man whose career was forged in the crucibles of high finance (a protégé of George Soros, no less), declared his personal stake in the ongoing trade war with China. "Martha, in case you don't know it, I’m actually a soybean farmer," he told ABC's Martha Raddatz. "So, I have felt this pain, too."

The statement hangs in the air, a piece of data that doesn't fit the model. Here we have the Secretary of the Treasury, a key figure in a hypothetical second Trump administration, negotiating the flow of global capital and averting a 100% tariff threat. Yet, he presents his primary credential for this task not as his decades of experience navigating complex financial markets, but as his alleged connection to the soil.

This isn't just a folksy aside. It's a calculated deployment of a narrative asset. In the world of finance, we call this "storytelling." You build a compelling narrative around a stock to influence investor perception, often highlighting a minor but relatable detail to distract from less favorable core metrics. And this is the part of the transcript that I find genuinely puzzling: Bessent’s "soybean farmer" identity is being deployed as the emotional anchor for a high-stakes geopolitical negotiation while a domestic crisis of his own administration's making spirals out of control back home.

Let's treat this like an earnings call. A CEO often uses the Q&A portion to reframe the narrative, and that's precisely what Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is doing. The "core business"—the functioning of the U.S. government—is hemorrhaging value. It's day 26 of a shutdown, federal workers are visiting food banks, and according to a recent report, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent says U.S. won't be able to pay military by Nov. 15 amid government shutdown. That’s a catastrophic failure in operational management.

So, what does a savvy executive do? He points to a promising, high-growth "emerging market." In this case, that's the China trade deal. Bessent paints a glowing picture: tariffs averted, "substantial agriculture purchases" secured, and a "fantastic meeting" on the horizon between the two leaders. He presents a "substantial framework" for a deal, a phrase that sounds solid but, without hard numbers, is functionally meaningless. It’s the political equivalent of announcing a "strategic partnership" without disclosing the terms. What, precisely, are "substantial" purchases? Is it a return to pre-tariff levels, or a marginal increase from the current baseline of nearly zero? The data is conveniently absent.

This is where the soybean farmer persona becomes so critical. It’s the humanizing data point meant to make the abstract promises of the China deal feel tangible and empathetic. It’s a shield against questions about the very real, quantifiable pain of the shutdown. When asked about meeting with Democrats to end the domestic crisis, Bessent is dismissive: "What good does it do?" He assigns 100% of the blame to Democrats, claiming they’ve dug in for political reasons (a claim that is hard to verify without internal polling data). There is no ownership, no shared responsibility. For the shutdown, he is a frustrated spectator. For the China deal, he is the protagonist.

The backdrop to all of this only amplifies the sense of unreality. While federal workers wonder about their next paycheck, the administration's primary focus in Washington appears to be the literal demolition of the White House's East Wing. The project, a $300 million privately funded ballroom, is a stunning visual metaphor. The administration is tearing down a piece of historic government infrastructure to build a venue for galas, all while the government itself has ceased to function. The optics are disastrous, yet the White House defends it by showing black-and-white photos of the West Wing's construction in 1902.

This is a masterclass in whataboutism, a tactic of narrative deflection. Don’t look at the rubble today; look at the construction from a century ago. Don’t look at the furloughed air traffic controllers; look at the successful framework we just negotiated in Malaysia. Don’t look at the Wall Street veteran running the Treasury; look at the humble soybean farmer who feels your pain.

The strategy is clear: segment the audience. For the base, the farmer persona and the tough talk on China resonate. It’s a story of a strong leader fighting for the heartland. For everyone else, the chaos of the shutdown and the absurdity of the ballroom project are meant to be obscured by the fog of partisan blame. The problem is that balance sheets don't care about stories. The cost of the shutdown is real and accumulating daily. Bessent himself notes it’s "starting to eat into the economy"—about 0.2% of GDP per week, if past shutdowns are any guide. To be more exact, some economists place it closer to 0.25%. That's a quantifiable drag that no amount of vague promises about future soybean sales can erase.

So, how does an analyst reconcile these conflicting data streams? Is Scott Bessent the savvy international negotiator he presents himself as, or the ineffective domestic manager his own words betray? Can he be both?

My analysis suggests that we're not looking at a person with a contradictory identity, but rather a highly skilled asset manager applying his trade to the political sphere. Scott Bessent isn't a farmer who happens to be Treasury Secretary. He is a Treasury Secretary who has identified the "farmer" narrative as an undervalued asset in the current political market. His job is not merely to manage the nation's finances but to manage the public's perception of those finances. The shutdown is a liability on his books. The China deal is an asset. The "soybean farmer" story is the leverage he's using to amplify the asset and write down the liability. It's a trade. And like any good trader, he's betting that the story will move the market before the underlying fundamentals force a correction.